Widening regional disparities in Europe

Widening regional disparities in Europe

Wealth disparities within EU countries were narrowing prior to the 2008 crisis, but since then the poorer regions have stopped catching up with the wealthiest ones.

“European countries converge at national level, but at the cost of a rising divergence within the countries” explain Joaquim Oliveira Head of the OECD Regional Development Policy Division in an interview with the FT.

According to Eurostat, the per capita output of the South of Spain- its poorest region – was about 57 per cent of that of the richest region, the community of Madrid. The South was catching up, peaking at 59 per cent of Madrid’s level in 2005, and remained largely stable until 2007, but the crisis hit the south of the country particularly hard, and in the four years to 2014 its GDP per capita fell by eleven percent compared to less than 5 per cent in the Madrid region.

Spanish regional divergence is also seen in unemployment data. Andalusia and Catalonia alone contributed over 40% of the increase in the number of young unemployed over the period 2007-2012, while the South accounted for about 30 per cent of the increase in overall unemployment between 2008 and 2014.

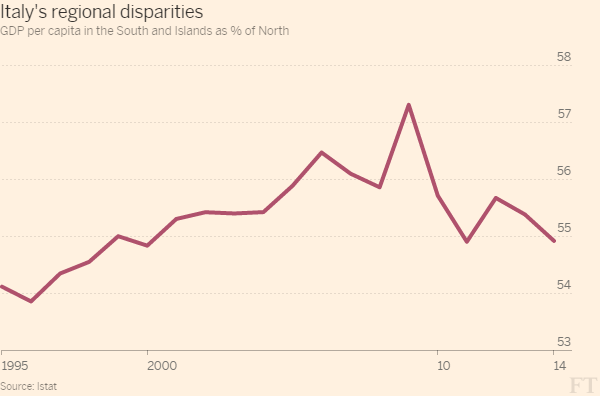

A similar story can be seen in Italy. Back in the mid-1990s, the South of the country – an area with long-running structural problems – had a GDP per capita of about 54 per cent of that of the North. This proportion slowly increased to a peak of over 57 per cent in 2009 and then dropped again to 2000 levels.

“One of the issues is that with the crisis investments collapsed” explains Dr. Oliveira. Public investments fell by 13 per cent in real terms across the OECD in the three years to 2012. Since about 72 per cent of public investment in the OECD is managed by sub-national governments, this has created a particular challenge for regions and localities. Moreover, public sector cuts are likely to have a bigger impact on poorer regions because of their over-reliance on public sector employment.

Emigration is also part of the story. According to the European Trade Union Institute: “rural and less developed European regions may find that they lose their most important resource, namely, people, without whom it will be far more difficult to close the development gap.”

While poorer regions have become relatively poorer within their respective countries, some of the best performing regions have been converging with each other. The per capita output of the region of Madrid was about 80 per cent of that of the north-east of Italy in 2000, but the proportion reached a similar level in 2007 and has remained stable since then.

This pattern extends beyond southern European countries. The metropolitan areas of Paris and London, for example, have outperformed other French and UK regions since the onset of the crisis.

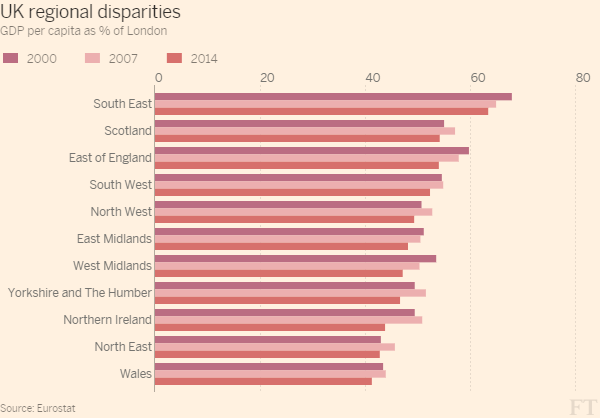

In the UK, the GDP per head of London accelerated away from other regions after 2007. Scotland and the North West were catching up with London before the crisis, but not so afterwards.

An OECD paper on regional policies states that “London’s productivity premium is outstanding, but more striking still is the weak performance of most other UK metropolitan areas. Few other cities appear to benefit from agglomeration economies or possible positive spill-overs from London. This suggests room to improve policies, starting at the national government level, but also addressing sub-national levels.” The UK government’s ‘Northern Powerhouse’ policy is an attempt to improve the performance of UK cities outside the capital.

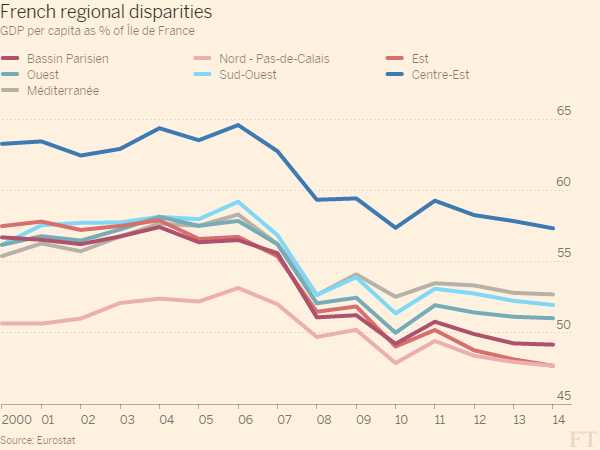

Similarly, in France the Paris region of Île de France has a level of GDP per capita about double that of the other regions and again, while there was some convergence before the crisis, the trend has reversed since then.

Greece and Germany have been exceptions to this trend, for quite opposite reasons.

In Greece, regional disparities continued to shrink during the recession, as GDP per capita collapsed across all regions.

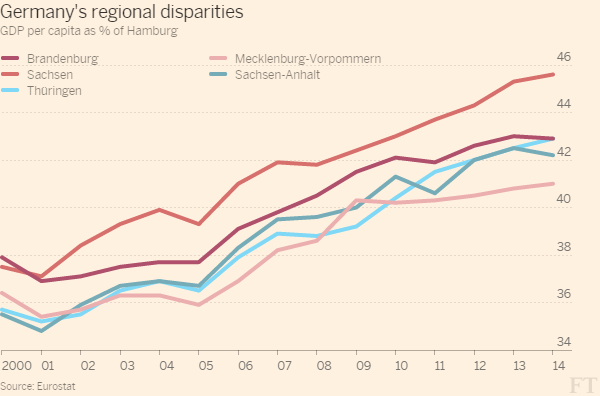

In Germany, eastern regions – the old pre-unification East Germany – had extremely low levels of GDP per capita compared to Hamburg, the wealthiest area, but the gap narrowed both before and after the crisis, and the differential is now comparable with that in many other Western European countries.

“This is what normally happens” comments Dr. Oliveira. “Spillovers from the top performers should make the poorer countries grow faster and catch up. We still don’t have a very good explanation of why the trend has stopped happening elsewhere”

No comments:

Post a Comment