How Italy got in (and out of) the debt trap

This week the European Commission let Italy off the hook, granting the country extra flexibility – to the tune of 14 billion euros – in its debt reduction targets for 2016.

The extra “flexibility” includes allowances for investments (0.25 per cent of GDP), for the refugees crisis (0.04 per cent of GDP) and for extra security measures (0.06 per cent of GDP). In return the Commission wants a ‘clear and credible commitment’ from Italy that the country will respect its budget targets in 2017.

How did Italy get to this point?

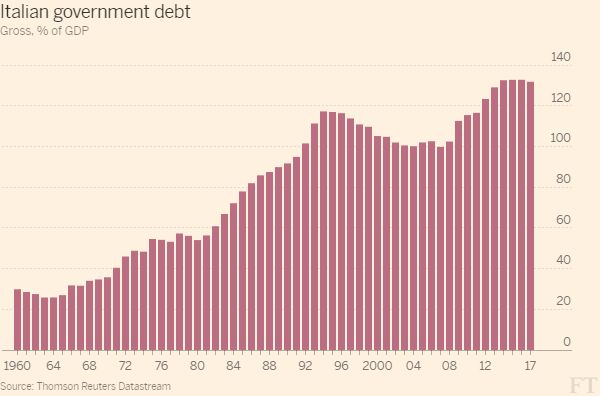

Italian public debt currently stands at 132.7 per cent of GDP – the second highest in Europe after Greece.

In the eighties Italian debt rose by 38 percentage points and by 1990 it had reached 92 per cent of GDP. It then experienced the largest drop in the post- World War II period and rose again after 2007, albeit for different reasons.

The legacy of the eighties

The debt explosion of the 80s is, at least in part, a story of bad management of public finances.

“The influence of political parties (..) has contributed to the widespread inefficiencies, to the proliferation of external technical bodies and to the fragmentation of public administration”, a 1997 OECD country survey explains.

Public expenditure was high also because of “inadequate controls, poor co-ordination among procurement agencies and collusion between suppliers and administration.” But this is just one part of the story.

In the eighties, the Bank of Italy introduced high policy rates- at 19 per cent compared to 7.5 per cent in Germany- as a way of reducing fluctuation in exchange rates ahead of the introduction of the single currency. But they also resulted in very high interest payments on the debt.

Despite the waste in the public finances, Italian government spending excluding interest payments increased less than other major European economies.

But, contrary to other European countries, in Italy the tax increases needed to finance this expenditure were delayed.

The result was a budget that for sixty years was never in surplus and that reached its worst levels -12 per cent of GDP – in the mid-eighties.

Italy finally reached a surplus in its fiscal balance (excluding interest payments) in 1992 thanks to a series of measures of fiscal consolidation. It has remained positive ever since, with the exception of 2009.

What now?

With around 4 per cent of GDP still being spent on paying interest on public debt – that’s double the OECD average and nearly four times what Germany pays – the overall budget is still in deficit.

A reduction in debt-to-GDP ratio is expected by 2017 – this should result in a further shrinking of interest payments, assuming interest rates remain low.

This would leave room for “some tax cuts or growth in non-interest expenditure” as the OECD wrote in its latest country survey, which could be crucial in fostering economic growth.

Economic growth is key

“Economic growth is the way out of the debt trap” explains Lorenzo Codogno, visiting professor at the LSE, chief economist at Micro Advisors and former director general at the Treasury of the Italian Ministry of Finance.

Indeed, the size of the economy is the denominator that inflates the debt-to-GDP ratio in times of falling economic output.

In the period which saw the fastest reduction of the debt-to-GDP ratio, real public debt actually increased more rapidly than after the global economic crisis.

But with sluggish economic growth, even milder increases in debt have resulted in a steep rise of the debt-to-GDP ratio.

But fostering growth is difficult

Measures of fiscal consolidation might reduce aggregate demand, and thus impinge on overall economic performance, although this is a controversial issue.

But Mr Codogno argues that “the issue of aggregate demand is much smaller now compared to 2011-2012. Economic growth should be promoted via structural reforms, rather than short term support to demand”.

Current and previous governments have already cut spending and “there are no low-hanging fruits left”. According to Mr Codogno the time has come to reduce public spending by “restructuring the way the government offers its services to citizens”. Reforms of public administration are underway, but “there are still plenty of inefficiencies that could be reduced”.

Italian debt is sustainable

“In the long term Italian public debt is one of the most sustainable in Europe”, argues Mauro Pisu, senior economist at OECD. Along with a series of measures intended to accelerate economic growth, he believes the cut in public spending, particularly on pensions, and a primary surplus among the highest in Europe have ensured this.

But Italy needs to get ready for when interest rates will go back to ‘normal levels’ resulting in higher interest payments and a budget which will be harder to balance.

Promising forecasts on the debt-to GDP ratio indicate that the country is on the right path out of its debt trap. Hopefully it’s also proceeding at the right speed.

No comments:

Post a Comment