Discontent among UK teachers drives recruitment crisis

“Start a new rewarding career this September” writes the Department for Education on a website inviting people to become teachers, “places are still available.” They might be available for a long time, if data on teachers’ satisfaction, recruitment and retention is to be considered.

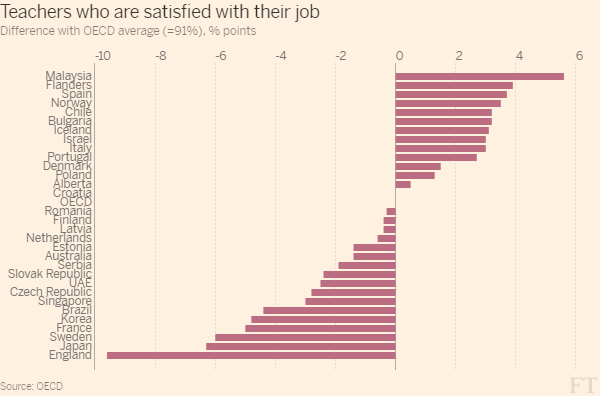

UK teachers were the least satisfied in an OECD survey of 5 million teachers across 34 advanced economies carried out in 2013. That’s ten percentage points less satisfied than the average.

And the mood seems to have deteriorated

Last year 67 per cent of teachers reported declining morale, and more than half were considering leaving the profession.

These days an even higher proportion of teachers – 83 per cent – is thinking of quitting according to research by the Association of Teachers & Lecturers (ATL) released in March.

Heavy workload

“Workload is a real issue” says Dr Mary Bousted, general secretary of ATL, in an interview with the Financial Times. “Experienced teachers are leaving the profession because they can’t stand the workload and the stress anymore.”

This finding is confirmed by teachers’ surveys which show that the volume of workload is the key reason for teachers planning to leave the profession.

Teachers in England spend more time in the classroom than most of their international peers. Moreover, in England teachers spend an average of 14 hours per week planning lessons and marking homework, that’s three hours longer than in the average of the OECD.

UK teachers are also burdened by “bureaucratic nonsense”, as Dr Bousted put it, referring to the time spent filling forms for accountability reasons.

Although the government has attempted to cut down on the workload by, amongst other measures, reducing the number of compulsory reports and plans for inspectors, the new curriculum and new policies “are placing a significant workload on teachers for the next 2 years” schools minister Nick Gibb admitted in a speech to the Association of School and College Leaders last month.

A curriculum which is “not fit for purpose”

The aim of the government’s curriculum reforms is to allow “all children, not just the offspring of the wealthy and privileged [to be] able to write fluent, cogent and grammatically correct English”.

But the majority of the teachers, and 70 per cent of head teachers, believe it is not fit for purpose. And three in four teachers believe that the policies behind the school curriculum and pupil assessments were narrow and uncreative.

“We have primary and secondary school curriculum that is highly inappropriate and ridiculously difficult”, says Dr Bousted. “A whole range of education experts, and teacher professionals, are opposed to the current curriculum and tests’”.

Other reforms were also poorly received by most teachers

Most teachers didn’t think that the proposed baseline tests for reception pupils would give a reliable measure of their progress.

And only a minority of British teachers (17 per cent) thought that turning schools into academies – independent, state-funded schools, which receive their funding directly from central government – would improve standards.

Both proposals were scrapped.

Government U-turns

So with reforms being introduced and scrapped it’s hardly surprising that the rapid pace of policy changes is why a third of teachers are considering leaving the profession.

Leaked tests being published and the delay in publishing a syllabus also add to the ‘storm of discontent’, as Dr Bousted called it, affecting UK teachers.

This leads us to a teacher shortage

Is the teachers’ discontent only temporary and linked to the “chaotic” implementation of reforms or is it a sign of more structural problems? It’s hard to say. Meanwhile, the teaching roles advertised are likely to remain unfilled.

Indeed in 2013 UK teachers had fewer years of working experience than most of their OECD counterparts. They were also generally younger, which suggests a lower retention rate within the profession.

In 2014, nearly 36,000 qualified teachers left the profession before retiring, 13 per cent more than in the previous year.

The number of vacancies more than tripled from 500 in 2011 to well over 1,700 in 2014.

This year recruiting targets were met in just three subjects: history, English and physical education. The remaining fourteen subjects faced a shortage of teachers including seven per cent gap in Maths, according to the National Audit Office.

Widening discontent

“Interestingly now, opposition is also coming from parents” says Dr. Bousted. And there are plenty of signs of this happening.

No comments:

Post a Comment