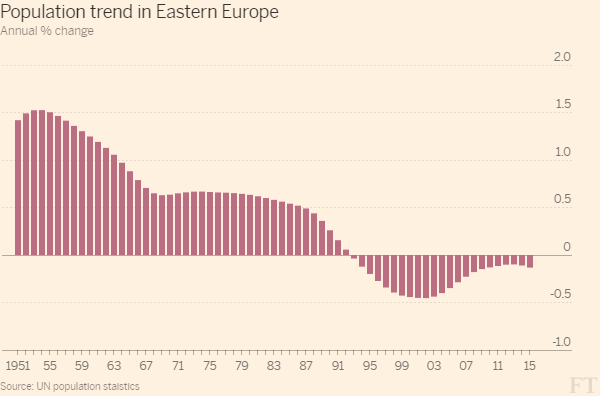

Eastern Europe has the largest population loss in modern history

Eastern Europe’s population is shrinking like no other regional population in modern history.

The population has declined dramatically in war ridden countries like Syria as well as in some advanced economies in peacetime, like Japan. But a population drop throughout a whole region and over decades has never been observed in the world since the 1950s with the exception of Southern Europe in the last five years and Eastern Europe over the last 25 consecutive years.

The UN estimated that there were about 292 million people in Eastern Europe last year, 18 million less than in the early 1990s, that’s more than the population of the Netherlands disappearing from the region. The fall corresponds to a drop of six per cent, give or take.

The contraction began after the fall of the Soviet bloc and accelerated until the early 2000s when it began to slow down.

Emigration

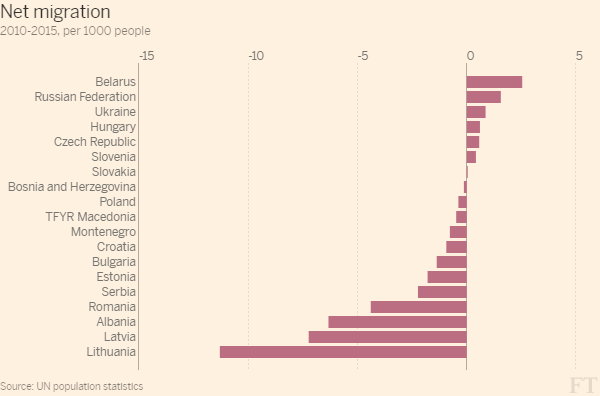

Emigration is one of the main reasons behind the decline. Eastern Europeans migrated to Western Europe, enticed by the prospect of higher earnings and better welfare systems. The main destinations for Poles, Latvians and Lithuanians were the UK and Ireland. Estonians left for Finland, Romanians went to Italy and Spain. More recently, Norway has emerged as a popular destination.

But this is not only a story of emigration made possible by the enlargement of the European Union. People from the region had begun emigrating even before Accession, and countries that are not part of the union have also seen a strong outflow.

Romania, for example, lost 9 per cent of its population in the fifteen years to 2005. In 1990 alone, nearly 100,000 Romanian citizens settled permanently abroad, with similar figures in the following few years. According to an OECD report, in the early days Romanian emigration largely concerned ethnic minorities. Most recently, it’s been job seekers. By 2007- the year in which Romania joined the EU- the majority of Romanian emigrants had already left the country.

Similarly, Bulgaria- which joined the EU in the same year- had a net migration rate of over eight per thousand in the first half of the 1990s, which progressively decreased to just over 1 per thousand in the last five years.

Albania, which is not an EU member, experienced an even larger outflow of migrants.

Falling fertility

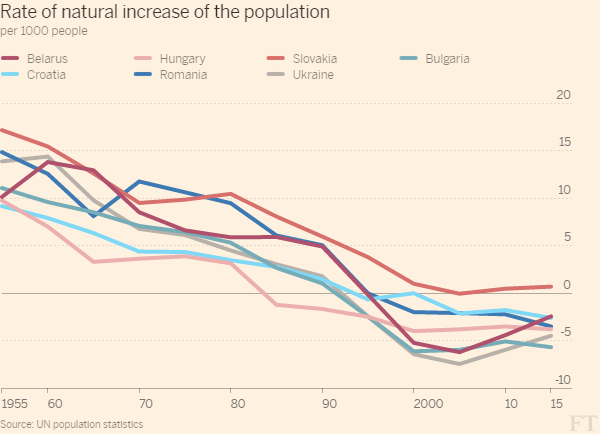

Those who stayed started having fewer children. Eastern European women had an average of 2.1 children each in the late eighties. Ten years later this had dropped to 1.2.

Economic and political uncertainty in the post-Soviet era had a significant effect on fertility rates, along with the absence of an adequate welfare system.

Although other countries, like Germany, experienced a similar drop in fertility, the effect is much bigger in countries which do not have similar levels of immigration. The result is that from the mid-1990s in most Eastern European countries deaths outnumbered births.

Institutions have started firing alarm bells

When the OECD looked into the impact of emigration in the Baltic and Eastern European countries it raised alarm over the long-term economic impact:

“While this [emigration] served as a safety valve in a time of poor employment opportunities and led to high levels of remittances, the longer term implications appear less positive: smaller working-age population, loss of educated youth, and skills shortages.”

The European Commission shares similar concerns. This is what it said of Romania:

“Strong outward migration, including of the highly-skilled workers, coupled with an ageing population represent a challenge to support a competitive economy.”

It is Eastern European countries which will suffer the steepest drops in the size of working-age population within Europe, according to the European Commission. By 2060 they will have the highest “old age dependency ratios”- meaning the proportion of older, inactive citizens relative to workers – in the region.

Policies are not helping much

Most Eastern European countries took measures to reverse these trends in fertility and emigration, with poor results. Poland gave cash benefits to those who had two or more children, one of many family policies trashed by Oxford University.

“The majority of extant family policies in CEE countries suffer from a variety of shortcomings that impede them from helping to generate optimal family welfare and to provide conditions for cohort fertility to increase,” the study says.

The OECD delivered a similar verdict for policies aimed at making emigrants return:

“Return policies have met with limited success (..). Job fairs aimed at emigrants from Romania did not lead to many returns. Polish programmes to bring back emigrants were stymied by insufficient planning, by negative economic conditions and by the requirement not to favour returnees over non-migrants.”

The narrowing of the wealth gap – more effective

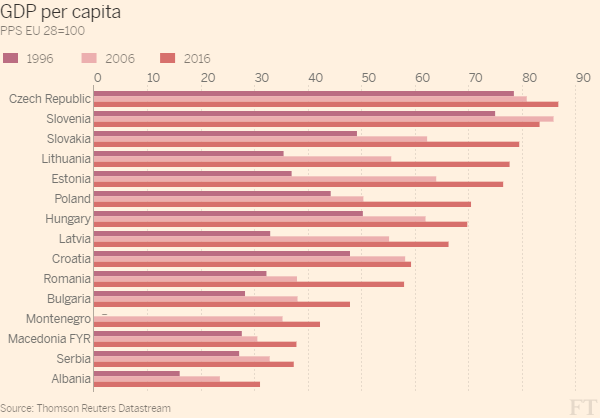

Most Eastern European economies are growing at an incredibly rapid pace, largely because they’re catching up.

What this means is that the difference in GDP per capita with Western Europe is narrowing. Broadly speaking, improving conditions in the region should reduce the incentives to emigrate. Better job opportunities and higher wealth should also lead to higher fertility rates.

The GDP per capita of the Czech Republic, Slovenia and Slovakia is now about eighty per cent or over that of the European Union. It used to be 50 per cent in Slovakia in the mid-1990s.

All these countries have seen their populations expand in the last decade.

But in poorer countries like Romania, Bulgaria, and Albania the size of the population is still declining.

But there are other behavioural factors, such as higher consumption of prescription and illegal drugs, a higher rate of traffic-related deaths and higher homicide rates.

But there are other behavioural factors, such as higher consumption of prescription and illegal drugs, a higher rate of traffic-related deaths and higher homicide rates.