The debate over big land data

How much land has been acquired for investment and agriculture over the past decade? The truth is nobody really knows.

Non-government organisations, media and academic publications have been assessing so-called land deals – where outsiders acquire huge tracts of land for commercial use – through field reports and by crowdsourcing data online.

A lot of recent documentation about land deals relies on data from Land Matrix, an international monitoring initiative, and Grain, an NGO based in Spain. Since June 2013, Land Matrix has been regularly compiling a global database on land deals. In 2012 Grain published a dataset of land acquisitions by foreign companies and governments, based on open-source data of agricultural land sales. Both plan to release updated data this year but researchers at both organisations told the Financial Times they believe there will be continued interest in big land acquisitions.

There is plenty of debate over the accuracy of this data. Official data sources vary widely from country to country, while land deals themselves are notoriously opaque and fluid. Media reports about the leasing or buying of land often lack clairity.

Carlos Oya, an academic at SOAS at the University of London, has urged caution about what passes for “fact” in land data and reports. A “fact” should be verifiable on the ground, he wrote in an academic paper on the methodology of the databases. However “in practice the evidence includes a mix of actual facts, perceptions, intentions, rumours, guesstimates (when the event is confirmed but its scale cannot be verified) and outright lies (from respondents or those who report the event)”.

In an interview with the FT Mr Oya said different regulations and levels of media interest could lead to over-reporting in areas such as Africa, and under-representation in others such as Latin America or Southeast Asia.

An oft-cited historical narrative is that land grabbing in the past decade have been spurred by concerns over food security and strategic planning, specifically the food price shock of 2007 when staple crop prices soared.

Data from Land Matrix seem to confirm this trend into 2009, a peak year. Land Matrix, which tracks deals bigger than 200 hectares, reported 140 transactions that accounted for 9m hectares, compared with 100 deals for about 2m hectares in 2006. We then see a steep drop in subsequent years; Saliou Niassy, Land Matrix co-ordinator, said the database is adjusted as acquisitions are verified, so there is a time lag in assessing what has happened more recently.

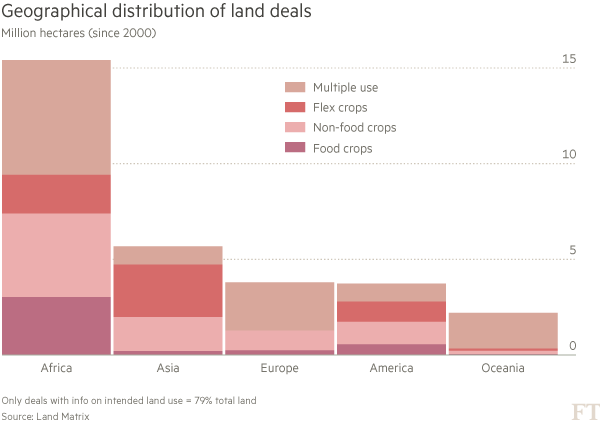

Overall, Land Matrix’s database accounts for 1,100 deals signed since 2000, involving nearly 40m hectares of land, an area larger than Germany. The most targeted region for acquisitions was Africa, followed by Asia. About 8 percent of the land involved in all deals was planned for tourism and conservation. Another 7 percent was aimed at producing biofuels.

So who investing in big land purchases? The Land Matrix data show that US investors are the most active. According to the database, US-based entities account for nearly 6m hectares bought or leased since 2000, much of it in Africa. Malaysian investors follow, largely acquiring land in Southeast Asia. Singapore investors targeted central Africa. Two Arab countries – UAE and Saudi Arabia–have concentrated on North Africa and Southeast Asia. Canada and the UK are among the top 10 investor countries with the majority of their land deals in Africa. Russian investors have been active in Ukraine and their home country.

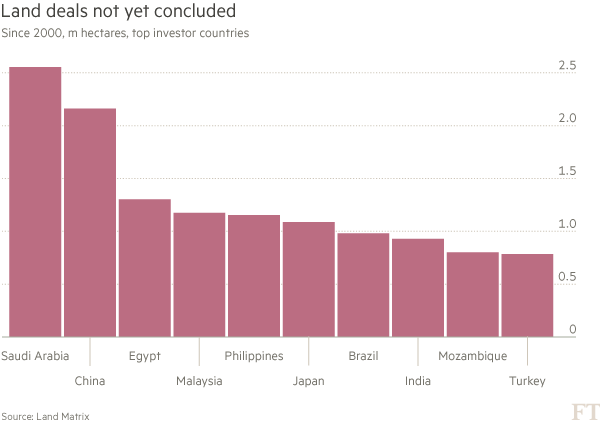

With “only” 1.4m hectares of land acquired since 2000,China is not among the top 10 investor countries in the database. It is, however, the second-largest country after Saudi Arabia pursuing deals that are under negotiation. It also ranks high – fourth out of 10 – among investor countries where negotiated land deals have failed.

Grain’s data, now five years old, dovetails with Land Matrix’s in finding Africa to be the primary target of acquisitions, and it notes increasing interest in Latin America, Asia and eastern Europe. However, Grain differs in that it points to Australia as the single country most targeted for acquisitions. Grain says agribusiness accounted for most deals overall, with financial companies and sovereign wealth funds tied to a third of them.

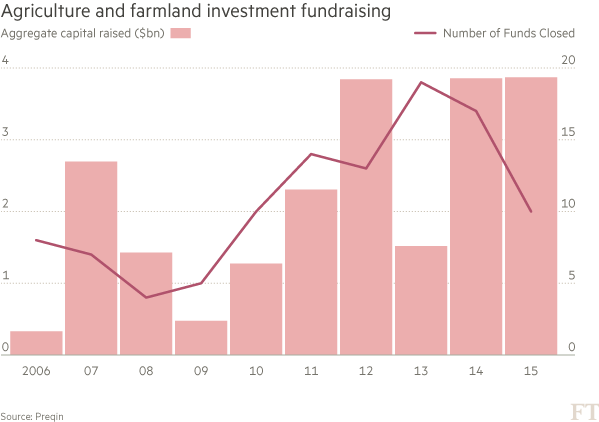

More recent analysis from Preqin, a data provider examining alternative assets, provides clear data supporting a global surge in acquisitions and investor interest. In 2009, only five agriculture or farmland funds raised a total of $500m. By 2015, 17 funds had raised $3.9bn, according to its analysis. Asset managers indicate that their interest is focused on regions that have an established grain-exporting history such as North America, Australia, New Zealand and Brazil.

Farmland is still evolving as an asset. Preqin notes that investors, intent on long-term strategies, might be spurred on by an “expectation of increased demand for food in the future due to global population growth” as well as the potential for “productivity gains (for) those with capital to invest in technology”.

No comments:

Post a Comment