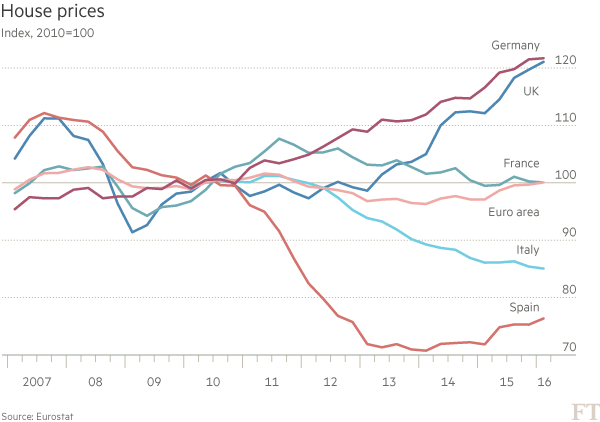

Seven years after the financial crisis, Italy’s property market has still not recovered. House prices in the country fell 1.2 per cent year-on-year in the first quarter of 2016, the only drop among major EU countries. In contrast, house prices in the region expanded at an average of 4 per cent over the same period.

Seven years after the financial crisis, Italy’s property market has still not recovered. House prices in the country fell 1.2 per cent year-on-year in the first quarter of 2016, the only drop among major EU countries. In contrast, house prices in the region expanded at an average of 4 per cent over the same period.

Why it matters

In 2014 there were approximately 100,000 fewer construction companies in Italy compared with 2008, a fall of 16 per cent. This ran in parallel to a fall in employment of almost 30 per cent.

The thousands of property-related businesses that folded as a result brought the already fragile banking system to its knees. Real estate and construction companies account for more than 40 per cent of corporate bad debts, up from 24 per cent in 2014 – a figure which is still rising.

In the 12 months to May more than 70 per cent of the rise in gross corporate bad debt was accounted for by the construction and real estate sector.

Moreover, on average two-thirds of bank loans are secured by personal guarantees or real estate collateral, so a reduction in price automatically reduces the debts’ coverage rate.

But why are house prices falling?

The house price trend is puzzling considering that the economy has been growing since the final quarter of 2014, employment is expanding, interest rates are at a record low, real household disposable income is finally rising again and foreign direct investments are at a record high.

“The problem is a large supply of unsold housing units” explains Luca Dondi, managing director at Nomisma, an Italian economic think-tank. More than 73 per cent of Italian households own their property, compared with 65 per cent in the UK, and more than two in three property transactions in the country are homeowners looking for better housing.

“When the crisis hit Italy, homeowners refused to sell their property at a discounted price as they were betting on a strong recovery of the market in the years ahead” Dr. Dondi told the Financial Times. The number of property transactions collapsed from 860,000 in 2006 to 403,000 in 2013, the lowest volume in 30 years. That’s a fall of 54 per cent.

Over the same period, house prices fell by just 7 per cent, according to Oxford Economics, a small drop when compared to that of Spain where prices dropped by over 23 per cent.

In 2013 sellers’ expectations changed as a result of the more stable financial and political conditions, as well as better economic measures. They finally started to sell. The number of residential properties that exchanged hands increased by 10 per cent in the two years to the end of 2015, but not at the asking price.

At the end of last year, almost two in three property sellers accepted a price reduction of more than 10 per cent of the asking price and it is becoming more common to slash prices by more than 30 per cent. Such drops were not observed even in the worst years of the housing market.

In other words, the change in sellers’ expectations resulted in a delayed drop in Italian house prices.

The number of residential properties built yearly has fallen by 85 per cent since 2005 and reached its lowest level last year of just 41,000 units. Despite the reduction in available housing units, “the amount of unsold properties accumulated since 2009 is likely to be very large and we expect a further drop in house prices in the months ahead” Dr. Dondi said.

Northern Cities are recovering better

As usual in post-crisis Italy, the south is suffering more than the north. The gap between price expectations and selling prices is much wider in the south, while the recovery in the residential property market is stronger in the northern cities.

In the first quarter of this year the number of properties sold in Milan, Genoa and Turin grew at an annual rate more than 26 per cent. Compare that with the 5 per cent growth rate of Palermo, the main city of the southern island of Sicily.

Milan is also the first city to show signs of property price stabilisation. In the first six months of this year, house prices grew marginally (+0.3 per cent) compared to the previous six months. Conversely, they continued to drop by 1.4 per cent in Palermo, according to data from Nomisma.

When will the property market recover?

The consensus is that the Italian property market is improving. Fitcth, the international ratings agency, expects “improving economic conditions […] should translate into stronger housing demand and higher volumes of real estate transactions” this year.

It also predicts “an increased availability of credit, stemming from the banking system for house purchase mortgages”. The Italian Associations of Builders believes this year will see the first expansion in residential investments since 2009. In their annual report on the building industry they note that house price reduction increased affordability, with positive effects on housing demand.

But it is still unclear if the strengthening of the property market will translate to price rises. Fitch expects house prices at the national level to “bottom out in 2016” with a further upside in 2017, “although below the overall inflation rate”. However nominal annual house prices growth is not expected to turn positive until 2018, according to Nomisma, nearly a decade since they started falling.