Ethnic minorities in the UK are more likely to go to university than their white British peers

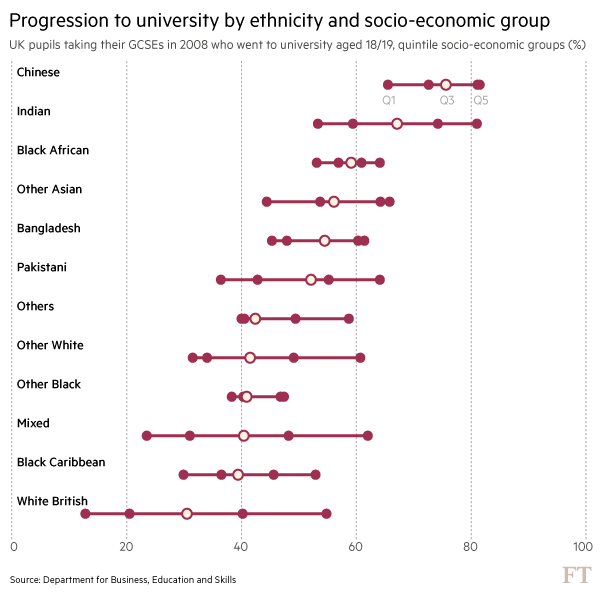

All ethnic minority groups in the UK are now significantly more likely to go to university than their white British counterparts. On average, amongst the cohort who sat their GCSEs in 2008, only one third of the white British population went to university in the academic year 2010-11 or 2011-12, compared to 75 per cent of ethnic Chinese pupils and 67 per cent of Indian students.

Progression to higher education also varies by socio-economic background with only 13 per cent of the white British pupils from the most deprived group progressing to university, compared to 55 per cent of the highest socio-economic group. This is the largest variation among all ethnic groups.

Moreover, progression to university of the most deprived white British group is by far the lowest among all groups. While only about one in ten of the most disadvantaged pupils go to University among the white British, the proportion rises to about half for the most deprived Indians and black Africans and increases further to two in three disadvantaged Chinese pupils. In fact, a larger proportion of disadvantaged Chinese goes to university than the wealthiest white British!

These are the results of research undertaken by researchers from the Institute for Fiscal Studies, funded by the Departments of Education and Business, Innovation and Skills (BIS), and published this week by BIS. The report also analyses the differences over time, from the cohort taking their GCSE in 2003, and reveals that participation amongst white British pupils increased less than for almost all other ethnic groups.

Black African pupils registered the stronger improvement with a gain of 11 percentage points in students progressing to university for the cohort 2008 compared to five years before. During this time the participation of black Caribbean and other black pupils overtook that of white British students.

The average progression to higher education is lower among the white British despite a smaller proportion being in the most deprived group (18% of white British are in the lowest socio-economic quintile of the whole population, compared to 40% of black Africans) and despite the fact that they tend to perform better at school that some other ethnic groups (the average score of key stage 2 results of the 2008 cohort for white British was 4.55 compared to 4.19 for the Pakistani group or 4.30 for the Black African pupils).

So what does explain the low rate of progression to university of the white British pupils, particularly among the lowest socio-economic group? It’s probably aspirations.

In a paper Migration and aspirations – are migrants trapped on a hedonic treadmill? The authors, Czaika and Vothknecht find that “Migrants have higher aspirations and we find strong evidence that while these aspirations are partly the result of the migration experience itself, they also had already existed before migration.” In another paper, Why the Difference? A Closer Look at Higher Education Minority Ethnic Students and Graduates, the authors Connor, Tyers and Modood surveyed potential entrants in higher education in the UK and found that minority ethic groups place greater expectation on higher education improving labour market positions than do the white British.

However, according to OECD data (Education at a Glance 2014) the earning gains and the employment rate differentials between people with tertiary education and those with secondary education are smaller in the UK than the average for OECD countries.

If ethnic minorities aspire to higher employment rates and higher earnings as a result of completing tertiary education, they are likely to achieve this, but the resultant improvements are not likely to be as pronounced as in other advanced economies.

Is there a sense in which the white British know that and don’t think that extra studying is worth the effort?